Five hundred pages into "Grant" I'm still enjoying it, although, truth be told, being 500 pages into "Grant" is like being 250 pages into a well edited book.

The same paragraph about whether or not Grant was drinking on a given day, or during a given journey appears over and over.

Mr. Chernow desperately needs an editor.

It's pretty obvious Chernow sat down with piles of books and files on every given major battle, every journey, journals from Grant's friend, Rawlins, books from historians Bruce Catton, James McPherson, and others and then pasted their comments into his paragraphs for that event.

The same sources keep getting quoted, often nearly the same quotes about whether or not Grant was drinking.

That being said, the picture which emerges of Grant and of those who mattered most to him, and to us--Sherman, Sheridan and Lincoln-- is worth the slog.

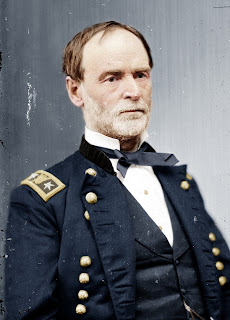

I have photos of Sherman on my walls, on coffee mugs, I like the image of him as implacable, and unwilling to accept the fantasy of war as something chivalrous.

One has only the excerpts from letters, the reports of historians, friends, adversaries, but it's not like you can see Gwen Ifil interview him on TV. It's not like you actually can have him over for dinner and judge for yourself.

On the other hand, there are enough reports of things he said at dinner parties, things he wrote, which line up. You can draw some tentative conclusions.

On thing seems pretty clear: William Tecumseh Sherman was a white supremacist.

He believed Negroes were simply inferior, lacked intelligence and courage, could not be taught. He said, on more than one occasion, when it came to Whites and Negroes there could only be a master/slave relationship. He said whenever you have Negroes, they destroy things; Whites build things.

As slaves left plantations in the wake of Sherman's march, and as they trailed after their savior--and many saw him as just that, the second coming of the mesiah--Sherman clearly considered them to be a nuisance, a rabble to be dealt with. Unlike Grant, who with more exposure to Blacks began to see them as human beings, and witnessing their valor in combat, Grant gained increased respect for them, Sherman was, from all we can see, unmoved.

And yet...There's always the "but." Sherman did plan to provide freed slaves in liberated Southern lands, plots of land from plantations now wrested from control of the slave owners; he gave individual slaves 40 acres each to farm, for the practical purpose of allowing them to support themselves without further government aide and also as a way of bringing imperious White plantations owners to the realization their claims to land were null and void. (This was later reversed by Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson.)

But where other Uninon generals embraced the idea of recruiting and using Negro troops--in particular Generals Thomas and Grant--Sherman would have none of it. The Negroes might be capable of farming but not soldiering Sherman apparently believed.

In the run up to the War, at a dinner party and among friends, Sherman opined that Blacks were better off as slaves than they had been in Africa, better off as slaves than they could be on their own. For the most part, the slaves were well treated Sherman told his dinner party companions, and the slaves were and ought to be happy.

All that was said just before the war. That was before his march, before he saw the joy of the newly freed slaves.

But even seeing their joy in liberation, Sherman took this as the expostulations of silly children.

All this may seem at odds with Sherman as one of the three major forces which ended slavery, but Sherman was, in fact, the embodiment of that Unionist who really did not give a hoot about the people involved, the slaves or even the slave owners. What animated him was the idea. The idea of "Union."

Union was tied up in the idea of order and loyalty and patriotism for Sherman, at least as far as you can discern from the records historians unearth.

While Lincoln and eventually Grant understood you could not have Union without an end to slavery, Sherman seemed to ignore this.

Whenever defenders of "The Lost Cause" want to sanitize the idea of exactly what that cause was, they refer to people like Sherman who, like so many Northerners entered the war simply because the idea of breaking up the Union was an anathema. And it was true, in the beginning many if not most of the Union soldiers had little sympathy for slaves. But, as Lincoln so famously described, whatever got people to join the war initially, ultimately everyone knew, in the end, slavery was the real cause of the war, if not for people like Sherman, for the people of the South and for enough of the North.

That mythological eminence, Robert E. Lee, was clearly a thorough going racist, who was appalled to see a colored officer on Grant's staff at Appomattox, and took his presence at the surrender ceremony as a personal insult. Sherman would have understood completely.

Where Grant was canny enough to refuse to allow Southern officers to take their "property" back home with them after they surrendered at Appomattox--because slaves were property--Sherman made no such order when he signed the surrender agreement with Johnston.

Lee had already surrendered in Virginia but Sherman had to chase down Johnston and demand the surrender of the Army of the Carolinas. Sherman attempted to allow the officers to keep their slaves and to leave slavery in place in the Carolinas.

Grant had to rush down to Durham, to nullify the agreement.

Oddly, Johnston had asked Sherman only for what Grant had given Lee, a pardon for his soldiers so they would not be tried as traitors and a promise not to molest them or prosecute them. But Sherman wanted to go beyond the simple surrender of an army; he wanted to settle the outstanding political issues which might threaten the peace after the army was disbanded, so he tried to guarantee the slave caste system would remain intact in the South.

After the Civil War finally wound down, after the last small Confederate armies scattered around the South had disbanded and only scattered guerrilla resistance remained, Sherman replaced Grant as commander of the Army and he pursued the Indian wars, and he was just as remorseless in his pursuit and subjugation of the American Indians as he had been of the Southern rebels.

Indians, after all, were not White.

So, once again, there are no heroes. No role models. There are only men who do heroic things and the same men often do despicable things.

We can look at them and understand the "Jungian thing," as Joker says in "Full Metal Jacket" when a stupid, officious colonel confronts him about the "Born to Kill" stenciled on Joker's helmet and the peace button on his collar. "The duality of man," says Joker. "You know."

The same paragraph about whether or not Grant was drinking on a given day, or during a given journey appears over and over.

Mr. Chernow desperately needs an editor.

It's pretty obvious Chernow sat down with piles of books and files on every given major battle, every journey, journals from Grant's friend, Rawlins, books from historians Bruce Catton, James McPherson, and others and then pasted their comments into his paragraphs for that event.

The same sources keep getting quoted, often nearly the same quotes about whether or not Grant was drinking.

That being said, the picture which emerges of Grant and of those who mattered most to him, and to us--Sherman, Sheridan and Lincoln-- is worth the slog.

I have photos of Sherman on my walls, on coffee mugs, I like the image of him as implacable, and unwilling to accept the fantasy of war as something chivalrous.

One has only the excerpts from letters, the reports of historians, friends, adversaries, but it's not like you can see Gwen Ifil interview him on TV. It's not like you actually can have him over for dinner and judge for yourself.

On the other hand, there are enough reports of things he said at dinner parties, things he wrote, which line up. You can draw some tentative conclusions.

On thing seems pretty clear: William Tecumseh Sherman was a white supremacist.

He believed Negroes were simply inferior, lacked intelligence and courage, could not be taught. He said, on more than one occasion, when it came to Whites and Negroes there could only be a master/slave relationship. He said whenever you have Negroes, they destroy things; Whites build things.

As slaves left plantations in the wake of Sherman's march, and as they trailed after their savior--and many saw him as just that, the second coming of the mesiah--Sherman clearly considered them to be a nuisance, a rabble to be dealt with. Unlike Grant, who with more exposure to Blacks began to see them as human beings, and witnessing their valor in combat, Grant gained increased respect for them, Sherman was, from all we can see, unmoved.

And yet...There's always the "but." Sherman did plan to provide freed slaves in liberated Southern lands, plots of land from plantations now wrested from control of the slave owners; he gave individual slaves 40 acres each to farm, for the practical purpose of allowing them to support themselves without further government aide and also as a way of bringing imperious White plantations owners to the realization their claims to land were null and void. (This was later reversed by Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson.)

But where other Uninon generals embraced the idea of recruiting and using Negro troops--in particular Generals Thomas and Grant--Sherman would have none of it. The Negroes might be capable of farming but not soldiering Sherman apparently believed.

In the run up to the War, at a dinner party and among friends, Sherman opined that Blacks were better off as slaves than they had been in Africa, better off as slaves than they could be on their own. For the most part, the slaves were well treated Sherman told his dinner party companions, and the slaves were and ought to be happy.

All that was said just before the war. That was before his march, before he saw the joy of the newly freed slaves.

But even seeing their joy in liberation, Sherman took this as the expostulations of silly children.

All this may seem at odds with Sherman as one of the three major forces which ended slavery, but Sherman was, in fact, the embodiment of that Unionist who really did not give a hoot about the people involved, the slaves or even the slave owners. What animated him was the idea. The idea of "Union."

Union was tied up in the idea of order and loyalty and patriotism for Sherman, at least as far as you can discern from the records historians unearth.

While Lincoln and eventually Grant understood you could not have Union without an end to slavery, Sherman seemed to ignore this.

Whenever defenders of "The Lost Cause" want to sanitize the idea of exactly what that cause was, they refer to people like Sherman who, like so many Northerners entered the war simply because the idea of breaking up the Union was an anathema. And it was true, in the beginning many if not most of the Union soldiers had little sympathy for slaves. But, as Lincoln so famously described, whatever got people to join the war initially, ultimately everyone knew, in the end, slavery was the real cause of the war, if not for people like Sherman, for the people of the South and for enough of the North.

That mythological eminence, Robert E. Lee, was clearly a thorough going racist, who was appalled to see a colored officer on Grant's staff at Appomattox, and took his presence at the surrender ceremony as a personal insult. Sherman would have understood completely.

Where Grant was canny enough to refuse to allow Southern officers to take their "property" back home with them after they surrendered at Appomattox--because slaves were property--Sherman made no such order when he signed the surrender agreement with Johnston.

Lee had already surrendered in Virginia but Sherman had to chase down Johnston and demand the surrender of the Army of the Carolinas. Sherman attempted to allow the officers to keep their slaves and to leave slavery in place in the Carolinas.

Grant had to rush down to Durham, to nullify the agreement.

Oddly, Johnston had asked Sherman only for what Grant had given Lee, a pardon for his soldiers so they would not be tried as traitors and a promise not to molest them or prosecute them. But Sherman wanted to go beyond the simple surrender of an army; he wanted to settle the outstanding political issues which might threaten the peace after the army was disbanded, so he tried to guarantee the slave caste system would remain intact in the South.

After the Civil War finally wound down, after the last small Confederate armies scattered around the South had disbanded and only scattered guerrilla resistance remained, Sherman replaced Grant as commander of the Army and he pursued the Indian wars, and he was just as remorseless in his pursuit and subjugation of the American Indians as he had been of the Southern rebels.

Indians, after all, were not White.

So, once again, there are no heroes. No role models. There are only men who do heroic things and the same men often do despicable things.

We can look at them and understand the "Jungian thing," as Joker says in "Full Metal Jacket" when a stupid, officious colonel confronts him about the "Born to Kill" stenciled on Joker's helmet and the peace button on his collar. "The duality of man," says Joker. "You know."

No comments:

Post a Comment