For him, lofty motives were infinitely less powerful , less trustworthy, less useful, than pure ones. Science was too difficult for people to engage in solely because...they wanted to help rid man of the burden of disease...They did it because they were absolutely certain it could be done and to prove to themselves and the world that they could do it first. They did it to bash their competitors, to think themselves divine, to win and to avoid the terrible, deathly anguish of losing. Backbreaking science and unblemished greed and raw fear, not moral correctness, would conquer AIDS. Boger was absolutely sure of that. He wanted to control it.--

Barry Werth, "The Billion Dollar Molecule"

|

| Dr. Anthony S. Fauci |

Reading Barry Werth's account of the Vertex corporation, a start up biotech company of the 1990's, and Tony Fauci's "On Call" simultaneously on my Kindle, going back and forth between the two is like tumbling back and forth between the hot sauna and rolling outside in the snow. Two entirely different sensations, but a singular experience.

|

| Joshua Boger |

Joshua Boger, who founded Vertex had the idea that drugs should and could be developed by knowing each atom and the structure, which includes its intricate folding, and using the known properties of the structure of molecules in biologic systems to design drugs.

One of the revelations of "The Billion Dollar Molecule," is the fact that most big drug companies find their drugs by shifting through soils and dust and other natural sources for molecules which they then purify and test for effects in living creatures. They do not build molecules atom by atom into structures they know will find receptors in viruses or human cells.

On some level, I knew that, as I was familiar with a drug called "Byetta" which was derived from Gila monster saliva, used to treat diabetes back in the late 1990's, which proved to be the great grandfather of the current blockbuster drugs, the GLP1 agonists, which include Ozempic and Zepbound.

Reading about the frenzy, the insanely long hours worked in the labs by Vertex's chemists, it was striking how similar it was to the crazy hours and tribulations medical interns of my era suffered. But the hours were imposed on the Vertex chemists not so much because this was the only way to do these experiments, but by competition imposed by Wall Street, the marketplace and money concerns.

I was introduced the "The Billion Dollar Molecule" at the last Endocrine Society meetings in Boston, by a chemist who showed a slide of the dust jacket, saying, if you want to know how drugs and Big Pharma actually work, read this book. It was the only time I've ever heard such a recommendation at a Society meeting, where the references are to refereed journals in small font.

Reading Dr. Anthony "Tony" Fauci's memoir, "On Call," is going from snow to sauna, or from the dark side of the moon to the bright side. I cannot say I am a friend of Dr. Fauci's, but I did know him as a third year medical student when he was Chief Resident in Medicine at the Cornell New York Hospital. He is 6 years old than I am and he graduated from Cornell University Medical College 7 years before me, and clearly the ethos of that place, as it existed in those antediluvian times clearly was burned into the man, like the college seals burned into the wooden backs of the chairs they sent out to graduates of their training programs.

Clearly, Tony Fauci is a hero worshiper and he wished to be a hero like the baseball heroes of his Brooklyn days. I lost count of the standing ovations he mentions and the celebrities he met at the White House (Bo Derek, a real 10!) and Bono and other famous stars. What is lost on the page, which may be retrieved in the audio book version, if he read it himself, is the inflection of wonder I heard when interviewing him years later in his office at the NIH, and when I encountered him at various parties and events around Washington.

When he tells you he was first in his class at Cornell University Medical College or how he got into Regis High School by scoring high on the entrance exam, there is an intimation of wonder, as if, "I hit that home run--can you believe it?"

Nobody he admires is mentioned without an attached, "world renown" or "widely respected" and brand name schools are part of what dazzles Dr. Fauci. His own college, Holy Cross had "one of the most respected premedical curricula in the country," and people are foremost or highly regarded. For Dr. Fauci, there is much which is sacred and celebrated. And that clearly provokes his detractors--Marjorie Taylor Greene instinctively knows she wants to undermine the whole notion of "respect" when it comes to "Mr. Fauci, because you're no doctor to me!" Fauci is an establishmentarian and the MAGA crowd are antiestablishmentarians.

And that drive of the five foot-seven inch boy with something to prove has never dimmed. He recounts how he donned the full space suit to be in the patient's room when NIH got its first Ebola patient. Fauci says he would never ask his troops to do something he would not do, and so there he was, leading from the front, like Captain Dick Winters in "The Band of Brothers."

There is a certain element of Teddy Roosevelt in all this. The charge up San Juan Hill in a space suit. But, as was said of Teddy Roosevelt: You must always remember Teddy remains six years old.

Of course, Colonel Sink restrains Captain Winters from leading the charge. Presumably, there is a reason we now believe important senior officers should not be lost to enemy action. We learned that much during the Civil War.

And yes, we hear a lot about Fauci running marathons and hiking along the canal along the Potomac River.

I can attest to the fact Fauci was in terrific physical condition well into his 50's at least: One morning, he flashed by me along the bicycle path on Macarthur Boulevard, shirtless, pumping away on his racing bicycle headed out toward Potomac, Maryland. He was lean, well muscled and flying. So whatever you may say about "short man syndrome" it served him well.

What can sound like relentless, interminable bragging sounds a little different to the ear of a CUMC alum, who heard the same stuff about dedicating yourself to the patient first, the importance of self sacrifice in medical practice, and all the rest, daily for years back then and the rest-- which means you are up at 2 AM, by the bedside, even if you do not have much more to offer than making sure the IV is working and the respirator settings are good. You remain visible and present.

For Tony Fauci appearing on all those TV shows, becoming really famous is justified not as self aggrandizement but as part of his job, to be the face of public health, to inform the public, to reassure and to educate. It's not about Fauci, personally, it's about the patient, about medicine and the health of the nation.

At Harvard nowadays, medical students are sent home at 10 PM so they can study for their quizzes and get enough sleep. I can only imagine what Dr. Fauci would say about that. I do know that hanging out on the wards, I learned far more and also different, more valuable and lasting stuff than I could possibly have learned from textbooks or journal articles which quickly went out of date. But what you saw on the wards happening to patients was learning which never expires. The Harvard, and certainly the Yale medical students I encountered in my time around these folks were smart in some ways, but were not doctors in the sense I knew doctors, or the way Fauci sees doctors--they always put number one ahead of everything else. They had to get A's on their quizzes, after all. Tony Fauci would say, "Sure, you need A's but you also need to stay up all night."

And, of course, there are some people you simply have to love because of the enemies they earn: And Dr. Fauci's account of Peter Navarro, who believed himself to be an expert in epidemiology and public health because he had a Ph.D. (in economics), who throws articles from Storm Front, the National Inquirer and the Wall Street Journal at Fauci which "prove" masks, quarantine and vaccines do not work, is just one of the odious cast to surface. There is, of course, Jim Jordan who berates Dr. Fauci for closing down schools and sports venues, thereby denying Americans of their "freedom," and, who can forget Marjorie Taylor Greene, much as we would like to?

My personal favorite did not make "On Call"--Brandon Fellows, a recently released ex-con who was imprisoned for 3 years for his attempt to overthrown the government on January 6, who mugged behind Dr. Fauci at a recent Congressional hearing, looking like that six year old son of Republican Rep John Rose (R-TN). Apparently this is all the GOP has to offer now.

In "Billion Dollar Molecule," Barry Werth reveals a culture at Vertex flowing down from Joshua Boger of enlightened selfishness--working hard to get rich and to win, and that brought progress in drugs to treat AIDS.

But Fauci is not primarily driven by money--he made among the highest salary in the federal government, but that was in the range of $400,000, not the millions the board members of Vertex or the guys at Goldman Saks make. And Fauci and his band of brothers also made progress in drugs for AIDS, motivated not by personal enrichment but by a personal connection with the suffering of the patients he admitted to the Clinical Center at NIH and to the gay community who he listened to.

Fauci is no less driven for personal reward. He is not operating on selfless altruism which Boger so dismisses with Ayn Rand contempt.

Fauci gets his reward from pursuing a heroic status; he sees himself charging up the San Juan Hill of AIDS, COVID, Zika virus and Ebola. But this does not rob the public or the individual patient of the benefits of his efforts.

Superman is no less heroic because he enjoys saving the day.

There is a story I asked Fauci about which persists at Cornell: The day he completed his Chief Residency, Fauci was ushered into the Department of Internal Medicine conference room, where the photos of every Chief Resident adorned the walls, and he was handed his certificate and his appointment to the faculty and staff of Cornell University Medical Center, which meant he could, as Chief Residents always did, open up his office on Park Avenue and go forth and live a rich and rewarding life of comfort and ease. Fauci said thanks but no thanks, to the stupefaction and dismay of the assembled dignitaries. A friend chased him down after the meeting and asked him, "Tony! How could you?"

And Tony reportedly said, "Someday, I'm going to be either very rich or very famous. But if I stay at Cornell, I'm going to be neither."

When I asked Fauci about his story, he flicked me one of his faint, economical smiles and said, "Well, they tell a lot of stories about me back at Cornell."

So I don't know if this story is true or not, but in a very real sense it is true to the perception about Dr. Fauci that being famous is important to him, in part because it is a part of his own story about himself, the little man who came from the most humble of circumstances, who grew up in a small apartment above his father's modest pharmacy, and wound up riding around in Presidential limousines and chatting up movie stars (Bo Derek!) and fighting off monsters like Ebola virus in a space suit.

But if that is his reward for all the hard, often frantic, demanding work he does, we all benefit from that. And we don't have to wait for a big company to make its money back before the patients get to benefit. If university folk or government servants can get their rewards from tenure or feeling heroic rather than from stock options, can that not drive the common good?

The platform for the COVID vaccine, after all, was achieved not by start up Wall Street backed companies, but by one very disparaged university faculty member (Katalin Kariko) who the University of Pennsylvania kept trying to fire, who they so marginalized she had a broom closet for an office, and her colleague (Drew Weissman, who Dr. Fauci says he "trained"), who managed to accommodate her while keeping his own job as the University of Pennsylvania tried to disown them, until they both got the Nobel prize for medicine at which point Penn claimed all the glory.

Great advances in drug therapy and in public health do not necessarily have to come from people being driven by greed, and promises of stock options.

In the case of the system Josh Boger argues for, the drug when it does emerge is tantalizingly attractive, but unavailable to help patients who want and need it now because the system which functions for profit cares nothing for patients.

In my own clinic, less than 20% of patients who need Ozempic, Mounjaro or Zepbound can afford them. I have to tell 80% of my patients, "Well, we have a family of drugs now that works exceptionally well. You could normalize your blood sugars, lose 80 pounds over the next nine months, safely, but it will cost you $800 a month, if you're lucky, out of pocket. Some of the weight loss may occur because you'll no longer be able to afford groceries."

Even if the patient jumped for that bargain, most of my patient's don't have $800 a month. They'd be homeless.

When Eli Lilly spoke with Frederick Banting and Charles Best about the process of getting a patent on insulin they sold their rights to insulin for $1, because they had a ward full of kids dying from type 1 diabetes. That was 1922. They had "discovered" insulin. They had spent a summer sweating away in a lab on the top of a hospital in Toronto, killing dogs, but finally identifying that single agent the pancreas makes which lowers blood sugar: insulin. They did not form a new company to capitalize on their discovery--they acted to get insulin produced at scale as quickly as possible to save a ward full of dying kids at their Toronto hospital.

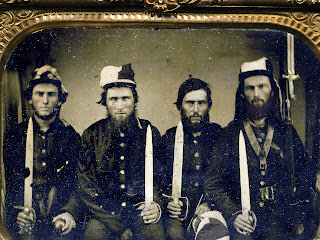

|

| Banting and Best and friend |

They did not need money to motivate their long hours and arduous efforts.

Can't imagine Joshua Boger doing that.

I can imagine Tony Fauci doing that.